September 17, 2009

While today's decision by the Obama administration to shelve our Eastern European missile defense system provides some hope for desperately needed improvement in Russian-American relations, the issue is far from dead. Proponents of the system already are accusing Obama of "appeasement," wrongly but effectively conjuring up fears of Russia as a modern-day Nazi Germany, bent on world domination.

Given the looming battle over missile defense, it behooves us to better understand why the Russians find this defensive system so offensive. To do that requires going beyond what most people think nuclear deterrence means and, instead, seeing its reality.

Neither the US nor Russia can use nuclear weapons against the other without being destroyed in retaliation, leading most people to believe that these weapons will never be used -- their very destructiveness seems to ensure the peace. But that view ignores the more subtle use of nuclear weapons in times of crisis. Because the Cuban Missile Crisis played this out farther than any other, it well illustrates the process and the danger.

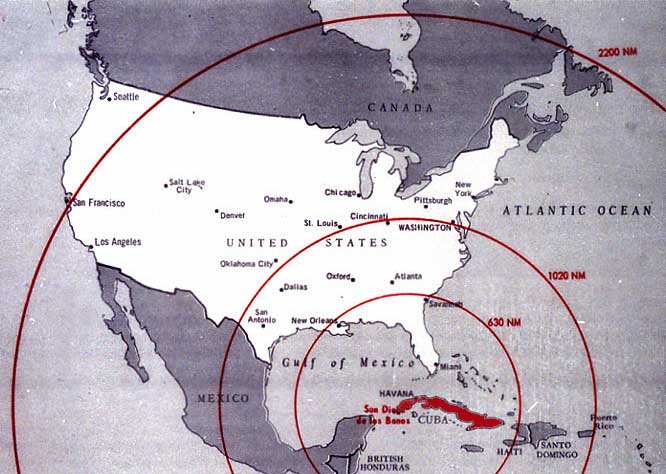

Khrushchev first contemplated deploying missiles in Cuba when he was confronted with a similar American threat in Turkey. We had deployed our Turkish missiles primarily as a "nuclear trip wire," a warning to the Russians not to become aggressive with Turkey, or else ...

Khrushchev's Cuban missiles served a similar purpose. The 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco had humiliated Kennedy and led to repeated calls within the US to invade Cuba in force and topple Castro. Khrushchev's Cuban missiles would serve as a Russian nuclear trip wire, a warning to us not to become aggressive with Cuba or else ...

Kennedy had to repeatedly resist demands for air strikes to destroy the Russian missiles, even though a likely Soviet response would have been a tit-for-tat strike on our Turkish missile bases. The US then would have been treaty-bound by Article 5 of NATO to react as if the Soviets had attacked American soil, even though doing so would have resulted in tens of millions of American casualties. Any rational American decision-making process would have concluded that it would be far better to back down and admit that our Turkish nuclear trip wire had been nothing but a bluff. The same was true for Russia's Cuban missiles.

Only by pretending to be insane enough to use its nuclear weapons and invite its own destruction can either side preserve the limited value that those weapons possess. In a crisis, each side therefore is tempted to continue its bluff, hoping the other will back down first. Such a standoff has been described as a game of nuclear chicken, with the loser -- and hopefully, there is only one -- being humiliated and losing power, as happened to Khrushchev.

The potential value of missile defense can be seen more clearly by recognizing that a Russian-American crisis is like a play with two actors, each supremely vulnerable and using every prop at its disposal to mask its nakedness. Neither our Turkish missiles nor the Soviets' Cuban missiles made a difference to 1962's balance of power, but they were useful props, giving an ability to project a perception of additional power.

The Russian thus have reason to fear that even a rudimentary, untested American missile defense will allow us to increase the intensity of our bluffs during a crisis. To be afraid of our missile defense, the Russians don't have to fear that it will give us a military advantage. They don't even have to fear that our leaders will mistakenly believe that it will. All they have to fear is that our leaders will act as if they believe that it does. In nuclear chicken, the first party to behave rationally loses, so having one more prop to use in our act is dangerous to Russia's interests.

At first, that might seem to favor the Eastern European missile defense -- at least from our vantage point. But appearing more irrational than the Russians is a highly questionable advantage since it increases the risk of a catastrophic outcome. Failure to weigh the chance of a small gain (coming out ahead in a crisis) against the risk of an infinite loss (destruction of our homeland) clearly can have disastrous consequences.

The need for our decision-making process to better balance potential gains and losses extends far beyond missile defense and national security. Lack of such a framework led financial institutions to take excessive risks, an error that is now costing us trillions of dollars. As expensive as that mistake was, it pales in comparison to what we will suffer if our nuclear weapons strategy proves as faulty. Before it is too late, let us learn from our now obvious economic mistakes and objectively balance the risks associated with changes in our nuclear weapons posture against the risk associated with threatening to destroy civilization.

* Martin E. Hellman is Professor Emeritus at Stanford University and a member of the National Academy of Engineering. His current project, applying risk analysis to nuclear deterrence, is described at NuclearRisk.org.

HOW YOU CAN HELP:

To create greater public awareness of this critical

issue, please forward this email to friends who

might be interested and encourage them to sign up

for future updates

via the JOIN US box in the left margin of this page

RESOURCES:

To better understand the problem and solution check out

Soaring, Cryptography and Nuclear Weapons

and our

Frequently Asked Questions.

Earlier emails to the group are on our Resource Page, along with other useful information. Email #4 is particularly relevant to this update. It describes how, in July 2008, this missile defense system created conditions very similar to those that led to the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Fortunately, tensions were defused before it created a full-blown crisis. But, until more prudent policies become the norm, the risk is still present.

SUBSCRIPTIONS:

To send a comment, change your email address, or unsubscribe please

send me a message at ___ (address deleted from web version to avoid spam).

REPRODUCING THIS PAGE:

Permission is granted to reproduce this page in whole or in part.

A reference to http://nuclearrisk.org/email24.php would be appreciated,

or in print to NuclearRisk.org.