Why worry about nuclear weapons now? Isn’t the Cold War over?

As a result of the improved Russian-American relations fostered by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, the world's nuclear stockpile has shrunk by about a factor of three. In that more benign environment, public concern about nuclear weapons has largely evaporated and progress, which was so promising twenty years ago, has slowed to a crawl and even seen some significant reverses in recent years. Society's complacency is unwarranted because, even after the massive reductions of the last two decades, there are still approximately 20,000 nuclear weapons in the world. The world is far more dangerous than most people think, and the threats of nuclear proliferation and nuclear terrorism have added dangerous, new dimensions to the risk.

Although clearly different in nature, nuclear terrorism and nuclear war are coupled. One of the possible triggers for a full-scale nuclear war is an act of nuclear terrorism. Particularly if directed against an American or Russian city, the resultant chaos has the potential to push the world over the nuclear cliff, much as a terrorist act in Sarajevo in 1914 was the spark that set off the First World War.

Conversely, the danger of nuclear terrorism is increased by the large number of nuclear weapons. With around 20,000 still in existence and many thousands of people involved in their maintenance, storage and security, the chance for error, theft or illicit sale is much too high. More than fifteen years after the bipartisan Nunn-Lugar Act initiated funding for dismantling and protecting "loose nukes" in the former Soviet Union, that effort is only about half complete [NTI 2007].

Loose nukes are not just a problem in Russia. On August 29, 2007, six American cruise missiles with dummy warheads were to be transported from North Dakota to Louisiana. After a day and a half it was discovered that missiles with real nuclear warheads had inadvertently been transferred instead [Washington Post 2007]. Until that mistake was uncovered, these six nuclear weapons were inadequately protected from theft by terrorists and others intent on obtaining such a prize.

If you haven't yet watched the video on our home page about the armed attack on South Africa's Pelindaba nuclear facility, I'd highly recommend it. That video clip communicates the danger of loose nukes better than any other description I've read or seen. To save you some clicks, I've repeated it below. And don't be scared off by its thirteen minute running time. If you have only a few minutes, watching just the beginning will still convey the main idea. Plus you're likely to come back when you have more time. It's that gripping!

Society is paying some attention to the possibility of nuclear terrorism, but the incidents described above show that such a disaster is still far too likely. This high risk and slow progress show that significantly more public concern and attention is needed to eliminate the threat of nuclear terrorism. Without that, as noted on our home page, a number of national security experts would not be surpirsed to see a nuclear terrorist attack on American soil within the next decade.

Proliferation already has added too many nations to the nuclear club, with North Korea being the most recent addition and Iran likely in the near future. While Iran protests that its nuclear program is only for peaceful uses, a number of factors provide strong evidence that, at a minimum, it seeks a nuclear breakout capability – the ability to rapidly build a nuclear weapon should it ever feel the need to do so. Given both the irrationality of some Iranian leaders and the existential threats against the regime made by the United States, a nuclear breakout capability may not be very different from Iran's actually possessing the weapons.

The threat of nuclear war has been almost entirely absent as a societal concern since the end of the Cold War. That is a grave mistake because Russian-American relations are still far too rocky. Over Russian objections and with President Clinton's blessing, NATO admitted the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland in 1999. Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia were added in 2004. Albania and Croatia were admitted in 2009, and President Bush pressed for Ukraine and Georgia to be admitted as rapidly as possible. President Obama has also kept open the possibility of Ukranian and Georgian membership even though the latter nation took actions in 2008 that led to war with Russia. (Most American media give the impresseion that Russia started that war. One of my blog posts on Georgia has relevant information, for example, that a European Union investigative commission concluded Georgia fired the first shots.) While the West sees NATO's expansion as a totally internal issue and resents any external interference in the process, Russia feels threatened and increasingly encircled by it.

Even without Georgia being in NATO, Sarah Palin has argued "that the U.S. should be prepared to go to war if Russia invades Georgia again." And the chance of a second round in that match is greater than most think. Georgian President Saakashvili's provocative statements and military actions. led conservative columnist Patrick Buchanan to wonder:

What is Saakashvili up to? He seems intent on provoking a new crisis to force NATO to stand with him and bring the United States in on his side – against Russia. Ultimate goal: Return the issue of his lost provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia back onto the world's front burner. While such a crisis may be in the interests of Saakashvili and his Russophobic U.S neoconservative retainers, it is the furthest thing from U.S. national interests.

Estonia, which is already a member of NATO, is involved in a deeply emotional conflict with Russia. Having been horribly subjugated when it was part of the Soviet Union, the newly independent Estonia has treated its large Russian-speaking minority (one third of the population) so poorly that Amnesty International issued a report entitled "Estonia: Every third person a potential victim of discrimination." [Amnesty International 2006]. Tensions reached a high in April 2007 when Estonia removed a memorial to the Russian troops who died defeating Hitler. Seen as a memorial to fallen soldier-liberators by Russia and many Russian-speaking residents of Estonia, the monument was a symbol of past Russian subjugation to the majority of ethnic Estonians. Soon after the memorial was removed, a cyber-attack caused a major disruption of Estonia's Internet access. This attack was believed to have emanated from within Russia, with many people believing the Russian government to be responsible. With Estonia a NATO member, this raised a very serious question:

"If a member state's communications centre is attacked with a missile, you call it an act of war. So what do you call it if the same installation is disabled with a cyber-attack?” asks a senior [NATO] official in Brussels. Estonia's defense ministry goes further: a spokesman compares the attacks to those launched against America on September 11th 2001. [The Economist, May 10, 2007]

If these tensions between Russia and Estonia escalate into a major crisis, we could face the prospect of having to either renege on our NATO obligations or threaten actions that would expose the entire United States to a nuclear attack. No one wants such a confrontation, but nuclear weapons lose all utility if we admit we can never use them. The U.S., Russia, and all other nuclear weapons states therefore behave as if these weapons have military utility, which is a very dangerous game in times of crisis.

Another irritant to relations is the differing Russian and American views of our deployment of a missile defense system in Europe. The U.S. says that the system is intended solely to protect against the possibility of an Iranian attack, so Russia has nothing to fear. Russia sees the deployment as threatening the credibility of its nuclear deterrent, and questions whether the missiles might really be offensive in nature [Moscow News Weekly, October 25, 2007]. Even former President Mikhail Gorbachev, hardly a Cold Warrior, has voiced concern:

Milos Zeman, the former Czech prime minister, said, 'What kind of Iran threat do you see? This is a system that is being created against Russia,' ... I don't think Zeman is alone in seeing this. We see this as well as he sees it [targeting Russia, not Iran]. [Moscow News Weekly, November 29, 2007]

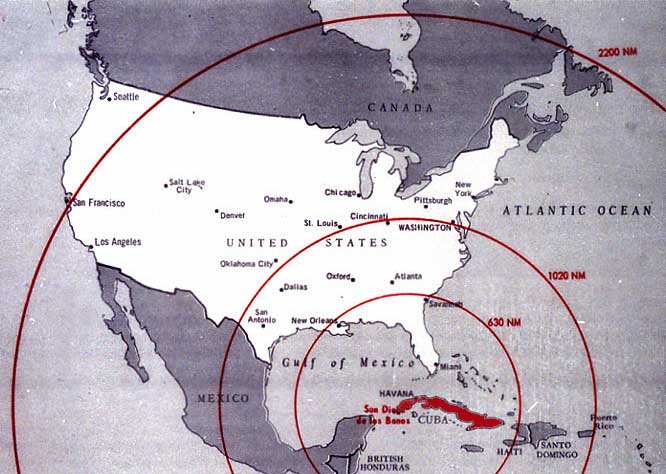

For reasons explained in my article Soaring, Cryptography and Nuclear Weapons, I have been concerned since 2007 that these differing views could lead to a repeat of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Somewhat ominously, several months after I first voiced that concern, Russian President Vladimir Putin likened the American deployment to the Cuban Missile Crisis:

I recall how things went in a similar situation in the mid 1960s. Similar actions by the Soviet Union, when it put rockets in Cuba, precipitated the Cuban Missile Crisis. For us the technological aspects of the situation are very similar. We have removed the remnants of our bases from Vietnam and dismantled them in Cuba, yet such threats for our country are today being created on our own borders. [Putin, October 26, 2007]Putin disclaimed that such a crisis could occur in the friendlier climate that currently exists, but those good relations were clearly fraying. Further evidence of the decline in Russian-American relations came in November 2007 when, partly in response to this missile defense system, Russia unilaterally "suspended" implementation of its commitments under the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe or CFE [Pravda, November 30, 2007]. In December 2007, events deteriorated further when Russia noted that it might target the system should it be deployed [Reuters, December 17, 2007].

Worse, in July 2008, a sequence of events started to unfold that could easily have led to a major Cuban crisis. But, because it stopped one step short of a full-blown crisis, almost no one is aware of it.

On January 30, 2008, at the Russia Forum in Moscow, former Russian Prime Minister Yevgeniy Primakov stated:

Russia's military doctrine, in conditions in which its armed forces are being reduced, is known to envisage the possibility of using nuclear weapons. But this is only on condition of an attack on it and its allies, and only against countries that also possess nuclear weapons. ... In this (Russia's) military doctrine is no different from the military doctrines of other nuclear states. [Primakov is probably referring to the fact that the U.S. has always rejected calls for a policy of "no first use" of nuclear weapons.] ... This policy – anti-Russian – increases the chances of "a fatal accident." The world may be made to face the threat of a global conflict without anyone whatsover wanting it. [Interfax, January 30, 2008]

In the U.S., while still a presidential candidate, Barak Obama had to back pedal after initially saying in an interview that he would not use nuclear weapons against terrorists in Afghanistan or Pakistan. His opponent for the Democratic nomination, Hillary Rodham Clinton, scored point with the public when she attacked that position by saying,“I think that presidents should be very careful at all times in discussing the use or non-use of nuclear weapons. Presidents, since the Cold War, have used nuclear deterrence to keep the peace. And I don’t believe that any president should make any blanket statements with respect to the use or non-use of nuclear weapons.” [New York Times, August 3, 2007]

Alhough the Cold War ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall, soon afterward an ominous chill began to descend on Russian-American relations. President Obama's effort to "press the reset button" on those relations has thawed relations somewhat, but there is still far to go. Realizing that goal is made harder by domestic opposition to what is often called Obama's appeasement of the Russians. There is also the question of what policies a new president or Congress might bring to this issue. When dealing with a threat of this magnitude, we need to look beyond just a four or eight year time horizon!

In summary, the nuclear threat didn't die with the end of the Cold War. At best, it merely went into hibernation.