Increasing Your Effectiveness

The five simple actions we are asking you to take involve bringing the nuclear risk to greater awareness within your social circle. Bringing up such a weighty topic may seem daunting at first, so this section contains some suggestions to make it easier.

Don't argue

If other people are uninterested or believe that society's

approach to nuclear weapons is fine as is, it's usually best

to drop the subject. Our goal is not to argue with those who

are comfortable with the nuclear status quo. Rather, we are

looking for those with open minds.

Reaching a tipping point within a group

requires only a small fraction

to become involved, so initially

most people will be uninterested.

Instead of wasting time arguing with someone

who has no chance of being part of that initial tipping point,

seek out others more open to the idea. And remember, no

effort is wasted. Some will respond the first time they hear

the idea, but most will have to hear it from several different

sources before they take it seriously. Treating those who disagree

with us with respect will maximize the chance they will respond

more positively the next time someone discusses the issue with them.

Keep the initial goal in mind

When discussing this issue

with someone new, it is best

to talk solely in terms of creating awareness about the

need to reduce the risk posed by nuclear weapons. So long

as society sees only benefits to possessing these weapons,

specific goals – especially long-range ones, such as

nuclear disarmament – will sound

naive and unachievable to most people. Only after

society becomes aware of the need for change will

specific solutions be seriously considered.

Stay focused

Trying to change the whole nation's thinking at

once is an unachievable goal. We are therefore

emphasizing creating small "pockets of nuclear awareness"

that then can spread more widely. For the reasons

explained on

that portion

of this web site,

you will be much more effective if you focus

most of your efforts on a small group to which

you belong, such as a school

or church. Reaching a tipping point in such a group

is well within our means, whereas diffusing

our efforts too broadly will produce little

of value.

Stay connected

Because we are social animals, it will increase your

effectiveness and that of others in your "pocket

of awareness" (e.g., a dorm, neighborhood or church group)

if you meet regularly to exchange views. No matter how important

an issue may be, it's hard to maintain motivation if you are the only one in

your social milieu who is concerned about it.

Keep it apolitical

Much of the current momentum for re-examining our nuclear

weapons strategies can be traced to

a 2007 Opinion Editorial

by George Shultz, William Perry, Henry Kissinger and Sam Nunn.

This support from four senior statesmen, with two

being Democrats and two being Republicans, emphasizes

the non-partisan nature of the issue. While President

Obama joined that effort with his

April 2009 Prague speech,

it is more effective to tie our effort to the bipartisan effort.

If you have not yet watched the 8-minute extended trailer of

Nuclear Tipping Point, featuring these four senior

statesmen, it is well worth the time:

Watch four senior statesmen – George Shultz, William Perry, Henry Kissinger and Sam Nunn – eloquently call for an urgent reassessment of our nuclear weapons strategy. This 8 minute extended trailer is taken from their full-length movie which is available on DVD, free of charge.

Emphasize support from experienced military leaders

Market research

has shown that people

tend to fear that those in favor of changing our nuclear weapons

policies are naive, and guided primarily by moral arguments that

are inapplicable in a dangerous world. Emphasizing that hard-headed

military leaders are in the forefront of this effort, and are convinced

it will enhance our national security, helps overcome

those concerns. Gen. Colin Powell was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of

Staff under the first President Bush, Bill Perry was Secretary of Defense

under President Clinton, Sam Nunn was head

of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Henry Kissinger was Nixon's

National Security Advisor, and George Shultz was Secretary

of State under President Reagan.

You Don't Need to Have All the Answers

Our goal is not to advance a particular solution, such

as nuclear disarmament or world peace. Rather our goal

is to get society to recognize the unacceptable risk it

faces from relying on nuclear weapons so that it will

then be motivated to discover how best to solve the problem.

The solution will require a number of steps, with

the later ones only becoming possible in the changed

environment produced by those taken earlier. So, even if

you had a crystal ball and could tell someone how the

solution will occur, it would sound unbelievable from

our current vantage point.

Become convinced – and therefore convincing

To be effective, you need to become secure in your

conviction that a reexamination of our nuclear weapons

strategy is urgently needed. A good place to start

is with a simple analogy that I call

The Man in the TNT Vest, featured on our

home page.

After integrating those ideas, our

resource page

is the next place to visit.

Emphasize the positive

If we talk only about nuclear catastrophe, we will

depress people, whereas we need to energize them. When giving talks on this

subject, I often start out by telling the audience I've got good news and bad

news. The bad news is that our current approach to nuclear weapons is

headed for disaster. The good news is that we're going to have to change

that approach, and most people are not really happy with Mutually Assured Destruction.

Defusing the nuclear threat has another major benefit in that it will require

a significant reduction in the level of violence around the world. The previous

section of this Nuclear Reader offers additional positive views.

Emphasize our ability to change

Prof. Carol Dweck

of Stanford's Psychology Department has studied how different

people respond when confronted with a challenge that exceeds their current abilities.

Some people take on the challenge even though that might mean failing, while

others shy away. While Dweck's research has focused

on individual abilities, the same ideas seem applicable to a person's

view of humanity as a whole, and a conversation I had with her supported that

view. Extended in that way, her research shows that if someone believes

human nature is fixed and immutable,

then bringing up your concern with the nuclear threat will tend to fall on deaf

ears. But such people tend to become more receptive if we emphasize the tremendous

capacity that human beings have for change. See section

4 of this Nuclear Reader for examples.

Emphasize the long-term process

At the end of the Cold War, hard-won public support for

changing our nuclear weapons posture evaporated almost

overnight in the mistaken belief that the problem had been

solved. To avoid a similar loss of momentum this time, we

must keep the long-term nature of the goal firmly in mind.

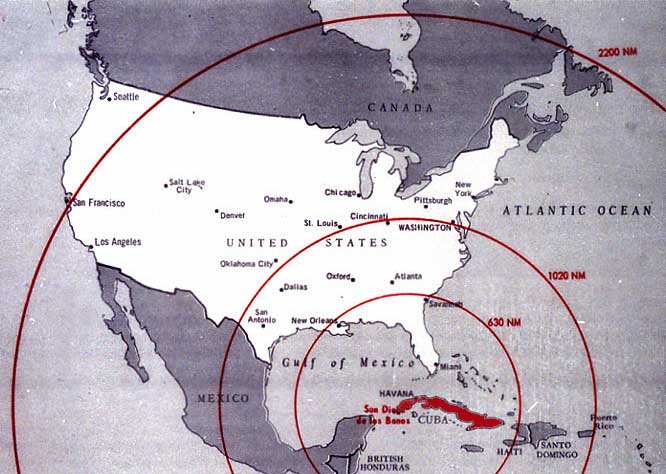

My research indicates that the risk we face from nuclear

weapons must be reduced by at least a factor of 1,000,

so the solution will occur in a multi-step, long-term

process, not in one fell swoop.

Be of goodwill

Ill will, judgment and blame play a major role

in perpetuating the nuclear threat. If we judge

those who disagree with us, we mirror the problem,

not the solution. If we have goodwill toward those

who disagree with us, we will be much more effective

advocates for change. When someone says something

that sounds outlandish to me, I try to remember

how outlandishly I once saw this issue.

Act as if your life depends on it

It does.